First to Fight:

The Devastators of Jaluit Atoll

First to fight

The Devastators of Jaluit Atoll

Eight weeks after disaster struck at Pearl Harbor, American naval Aviators took the fight to the enemy for the first time in World War II. Admiral Chester Nimitz (Commander in Chief of the US Pacific Fleet) ordered a series of offensive operations in the Japanese-controlled Marshall Islands, beginning at Jaluit Atoll, administrative center of Imperial power in the region. Eleven Devastator bombers from Torpedo Squadron Five (VT-5) flew in the vanguard of a surprise raid on enemy shipping and shore installations at the remote island. Four of those aircraft failed to return, but two would be seen again more than 50 years later.

The pair of planes that would eventually come to be known as the Devastators of Jaluit Atoll were not given individual names while in service. Instead, like most US naval aircraft of the era, they were referred to simply by their BuNo (Bureau of Aeronautics number) and the unique squadron code emblazoned on the side of their fuselage. BuNo 0298, the 32nd Devastator built by Douglas Aircraft Company in 1937, carried the designation “5-T-7” while BuNo 1515 was among the last few TBDs delivered as part of a limited late production run in 1939 and assigned the identifier “5-T-6”

In the predawn darkness of 1 February 1942 crews from Torpedo Five manned their planes on board the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown (CV-5), as the flagship of Rear Admiral Frank Fletcher’s Task Force 17 (TF17) rapidly closed the range to their objective. Lt. Harlan T. “Dub” Johnson, the squadron’s Executive Officer, was the pilot of BuNo 0298, while Ens Herbert R, Hein, Jr, one of VT-5’s most junior officers, took the controls of BuNo 1515. The weather at the time was ominous, with towering thunder clouds split by frequent streaks of lighting looming in the direction of Jaluit and just enough moonlight penetrating through the overcast to provide a sufficient horizon for take-off.

The mission was dogged by trouble from the start. One of the Devastators (5-T-9) was forced to abort almost immediately when its main landing gear failed to retract. Sadly, due to the poor visibility, two other TBDs (5-T-8 and 5-T-10) collided in midair and were lost with all hands, their passing marked by a dull orange flash in the gloom. The rest of the strike group pressed on, plunging through scattered clouds and rain that further broke up their formations, causing many of the planes to lose sight of one another and proceed independently.

On reaching Jaluit, the attackers found their targets obscured by a low ceiling and passing squalls. The Devastators, which had been armed and configured for this mission as level bombers, were forced to drop below 1,000 feet to release their ordnance. Poor visibility frustrated the bombardiers’ aim and also hindered damage assessments (though post-war analysis of Japanese records indicates it was relatively light). Admiral Fletcher canceled a planned follow up assault due to the unfavorable weather conditions and challenging navigation. Some of the Yorktown’s planes reportedly landed back aboard the carrier after that morning’s sortie with only a couple gallons of fuel to spare.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the chaos and confusion over Jaluit, Ens Hein had formed up on his XO’s wing as Lt. Johnson set out to rendezvous with their ship. However, after a short, but critical interval, the pilots came to the sickening realization that they’d mistakenly been flying a reciprocal course, headed away from the safety of the task force and burning through their already scant fuel reserves. Johnson calculated that he and his squadron mates would certainly splash in the trackless ocean wastes with dry tanks before reaching their goal and doubted Admiral Fletcher could risk detaching an escort vessel to come looking for them. With no better option, the fliers returned to Jaluit Atoll. Lt. Johnson led the way in BuNo 0298, choosing to deliberately set his plane down in the water on the far western edge of the lagoon. Ens Hein was next, ditching BuNo 1515 about 100 yards away.

This is 5-T-7. 5-T-7 and 5-T-6 are landing at Jaluit. Are landing alongside one of the northwestern islands of Jaluit. That is all.

-Text of final message received by Yorktown radio operators from Lt. Harlan Johnson, pilot of BuNo 0298

Johnson and his crew, auxiliary pilot/bombardier ACMM Charles E. Fosha and radioman/gunner RM1c James W. “Ace” Dalzell, scrambled into a three-man rubber boat and then ensured BuNo 0298 sank out of reach by shooting and slashing at the Devastator’s wing-mounted emergency “flotation bags” with a combination of .45 caliber gunfire and a sharpened bayonet kept on board for that purpose. The plane’s top secret Norden bombsight had been detached and thrown into the deep sea while still in flight to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. On board BuNo 1515, Hein and his men, AOM 3c Joseph D. Strahl and S1c Marshall E. “Windy” Windham took similar steps to disable and dispose of the downed aircraft, but in the process, their inflatable life raft was punctured by the sinking plane’s protruding antenna post. All six men from both Devastators then had to crowd into or cling to the sole remaining boat and strike out for the nearest patch of land, a sparsely populated islet on Jaluit’s fringing reef known as Pinglap.

The water-logged Aviators, after paddling for hours, finally managed to struggle ashore where they were kindly taken in, fed and sheltered by local Marshallese villagers. In the morning, the marooned Navy men spread out and scoured the area for a small boat or canoe that they might sail back to Allied territory, but found nothing. Their slim hopes of evasion faded as a Japanese seaplane repeatedly overflew their position and then were dashed entirely on the third day when a squad of Imperial marines landed on the tiny islet in search of the downed fliers. Without a realistic chance to fight or escape, the two stranded TBD crews emerged from cover and surrendered. The captives were immediately herded waist-deep into the waters of the lagoon for what appeared to be a summary execution until, following a few tense moments, an officer appeared and angrily put a stop to the proceedings. He then turned to the astonished airmen and announced (in English) that by “the graciousness of His Majesty the Emperor you are permitted to remain alive.”

As some of the first Americans taken prisoner by the Japanese during WWII, the six men were bound, loaded onto a flying boat, and transported to the Japanese home islands. They were then separated, sent to POW camps at Kobe, Osaka, and Zentsuji, and subjected to hard labor, torture, and privation for the duration. Miraculously, the crews from both Devastators survived their captivity to be reunited three and a half long years after the ditching at Jaluit Atoll. Each and every one of them returned home to their families.

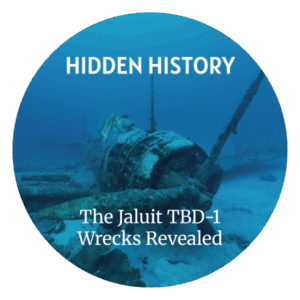

The planes however, remained where they fell. BuNo 0298 and BuNo 1515, would rest in the dark depths of the Jaluit lagoon for decades, awaiting the day that their full story could be told and, perhaps, when one of them may reemerge into the light.

Dive deeper – learn more about our mission by visiting one of the below topics.