TRIUMPH AND TRAGEGY:

The TBD-1 Story

Triumph and Tragedy

The TBD-1 Story

On first taking to the skies in 1935, the TBD-1 Devastator was a plane far ahead of its time. Even casual observers needed only a glimpse to see it as a major leap forward in aircraft design. Contrasting dramatically from the old-fashioned style biplanes then in naval service, the Devastator appeared sleek and modern, featuring all metal construction and a single low mounted wing that increased visibility and did away with the need for drag-inducing struts and bracing wires.

The important innovations didn’t end there. Devastators were the first plane type deployed with the US fleet to be fitted with a fully enclosed cockpit, sheltering the crew under an expansive and streamlined “greenhouse” canopy. They were also the first shipboard aircraft equipped with independent wheel brakes and introduced the concept of hydraulically powered folding wings, allowing for a greater number of planes to be packed onto crowded carrier decks. Additionally, their construction incorporated extensive use of Alclad® aluminum, a composite material that bonded high-purity aluminum sheets to a high-strength aluminum alloy core, making the TBD more more resistant to corrosion, ideal for operations in a harsh saltwater environment.

Powered by an advanced 850hp Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engine, the Devastator effectively doubled the performance of its predecessor in terms of speed, range, and service ceiling. Navy planners, impressed with the test results, placed an initial order for 114 production model Devastator aircraft, which the Douglas company delivered between 1937 and 1938. As these new mounts reached the fleet, word spread about what was considered a “hot ship,” and American naval Aviators eagerly clamored for coveted assignments to man one of its three crew positions as pilot, auxiliary pilot/bombardier, or radioman/gunner.

Many found the Devastator a joy to fly and were proud to know that the TBD-1 packed a serious punch. Configured as a level bomber, it could deliver a mixture of ordnance (weighing up to 1,000 lbs) from high altitude with the aid of the then top secret Norden bombsight. More crucially, in its primary role, the Devastator could carry a single torpedo with a 600 lb explosive warhead, skimming the wavetops and pressing close before releasing their payload to sink enemy vessels at sea. Each plane also carried a pair of .30 caliber Browning M1919 AN/M2 machine guns, one in the nose and the other on a flexible rear mount, for defense.

Carrier-based aviation, even under peacetime conditions, is a dangerous business. Over the course of less than two years, training mishaps and operational accidents took their toll on the US Navy’s supply of Devastators, prompting the Bureau of Aeronautics to place another order with Douglas for a late production run of 15 additional aircraft to replenish dwindling TBD stocks. This second batch of airplanes rolled out of the El Segundo, CA factory in mid-late 1939.

However, the tempo of aeronautical advancement was so lightning fast in those days, that the once-revolutionary Devastator was soon outclassed. Compared to the emerging threats it would face in a future conflict, the TBD-1 was deemed too slow, too lightly armored, and too vulnerable to being set on fire (due to a lack of self-sealing fuel tanks). In 1940, as war clouds loomed, the Navy selected Grumman Aircraft to develop the TBF Avenger as a more capable successor to the venerable Devastator.

USN torpedo squadrons had yet to transition to these new planes when the storm finally broke tthe following year and the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor drawing America into WWII. Nevertheless, displaying considerable skill, daring and imagination, TBD-1 crews gave a good account of themselves through countless patrols and a series of major engagements throughout the early, dark days of the war.

- 1 February 1942 Douglas Devastators from USS Yorktown (CV-5) and USS Enterprise (CV-6) flew as part of the very first offensive actions undertaken by the US Navy in WWII, in raids launched against Imperial Japanese forces at Jaluit, Kwajalein and Wotje in the Marshall Islands.

- 10 March 1942 Yorktown and USS Lexington (CV-2) dealt a surprise blow at Lae-Salamua on New Guinea’s east coast, sending their strike aircraft (which included heavily-laden TBDs) through a 7,500 foot pass in the towering Owen-Stanley mountain range to attack enemy shipping from a completely unexpected quarter.

- 7-8 May 1942 US and Imperial Japanese fleets met in the Coral Sea for the first naval clash in history in which the opposing vessels never sighted one another. The outcome was entirely decided by aircraft, including Devastators flying once again from Lexington and Yorktown, which contributed significantly to the sinking of the IJN light carrier Shōhō (祥鳳, “Happy Phoenix”). Though the Lexington was also sunk, along with its full complement of TBDs, the Japanese were forced to abandon invasion plans for Port Morseby, New Guinea and to set their sights elsewhere.

Through it all, USN Devastator squadrons had performed well, hampered mainly by the shockingly poor performance of their chief weapon, the Mark 13 aerial torpedo. Hard earned combat experience revealed the Mk 13 to be fragile and temperamental. It had an alarming tendency to break up on entering the water unless released at low speeds and altitudes, leaving the TBDs dangerously exposed on approach. Even when dropped successfully, the torpedoes often ran errantly or failed to explode on striking their intended target.

And the Devastator crews’ greatest trial was still to come. On 4 June 1942 a massive Japanese fleet moved to seize Midway Atoll, a vital base northwest of Hawaii. A scratch naval force centered on the three remaining US carriers in the Pacific, Enterprise, USS Hornet (CV-8), and a hastily repaired Yorktown, was sent to oppose it. With fearful odds against them, the Americans would face off against the cream of Imperial Japan’s First Air Fleet, the Kido Butai (or “Mobile Striking Force”), which had marauded seemingly at will in the six months since the disaster at Pearl Harbor.

Fully aware of both the dire situation and the shortcomings of their planes, US Navy TBD crews were resolved to carry on. Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron, commanding officer of USS Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron Eight (VT-8) summed up this spirit of grim determination in a final briefing to his men, concluding, “.. I actually believe that under these conditions we are the best in the world. My greatest hope is that we encounter a favorable tactical situation, but if we don’t, and the worst comes to the worst, I want each of us to do his utmost to destroy our enemies. If there is only one plane left to make a final run-in, I want that man to go in and get a hit, May God be with us all. Good luck, happy landings, and give ’em hell.”

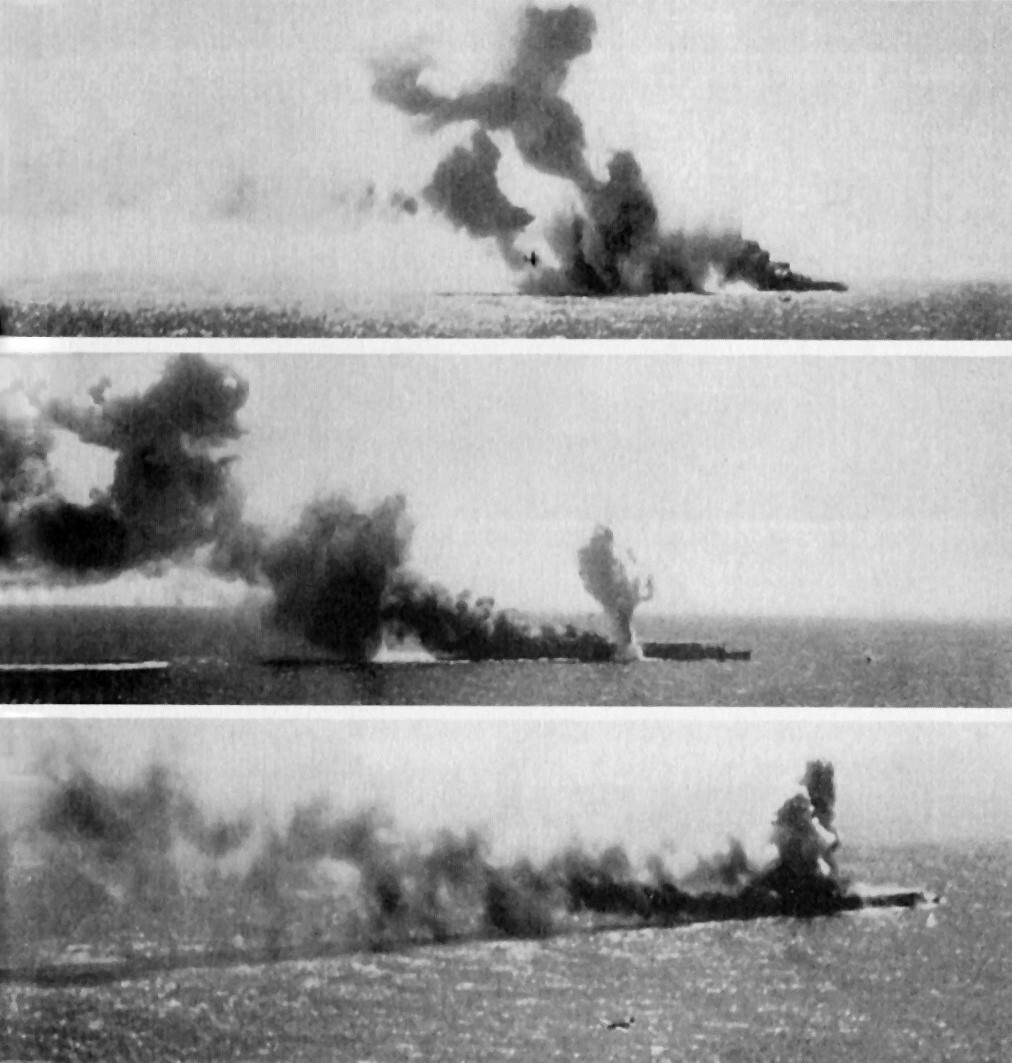

As the battle unfolded, it appeared as if “the worst” had indeed come to pass. The attacking Devastator squadrons suffered badly. One after the other they assaulted an alerted and well defended enemy. And one after the other, torn and burning TBDs fell into the sea. Out of a total 41 torpedo planes launched by American task forces against the Japanese fleet that morning, 35 of them never returned. Each and every Devastator from VT-8 was shot down with the loss of all but one man, Ensign George H. Gay, USNR. Not a single US torpedo found its mark.

Incredibly, this selfless sacrifice by Devastator crews would ultimately help bring about a famous victory. Their relentless attacks kept the enemy’s ships on the defensive, taking evasive action, while delaying the launch of a counterstrike against the American fleet. Additionally, much of the Japanese fighter cover had been drawn down to sea level and forced to expend most of its ammunition in dealing with the torpedo threat, when the scout/bombing squadrons from Enterprise and Yorktown arrived on scene at high altitude. These dive bombers swept down almost unopposed and, in a stunning reversal of fortune, quickly reduced three out of four Japanese carriers to flaming wrecks. By the time the fight was over two days later, the USN had traded Yorktown for the last of the enemy flattops and won what is rightly recognized as the pivotal battle of WWII in the Pacific.

After Midway, the few dozen remaining Devastators in the US Navy were quietly withdrawn from front-line service. They were relegated to stateside training duties and used as squadron hacks. By 1944, with the nation still at war, the last of the obsolete TBD-1s were stricken and scrapped, their materials recycled for use in building new and more modern aircraft.

In the years that followed, the courage and devotion to duty demonstrated by Devastator crews during WWII would take on near-mythic status. As the desire to commemorate their service by saving one airframe grew, so did the realization that no examples of the type were left to be set aside .. at least not on land. The quest to preserve a TBD would inevitably lead underwater.

Dive deeper – learn more about our mission phases by visiting one of the below topics.