Hidden History

The Jaluit TBD-1 Wrecks Revealed

Hidden History

The Jaluit TBD-1 Wrecks Revealed

The Devastators ditched at Jaluit Atoll during WWII would remain hidden from sight until the close of the 20th century when, in 1997, a cultural heritage survey sponsored by the Marshall Islands Historic Preservation Office discovered the wreckage of Dub Johnson’s BuNo 0298 resting on a submerged reef face near the islet of Pinglap. Shortly thereafter, a pair of American ex-pat divers (Matt Holly and Brian Kirk) living in the RMI capital of Majuro managed to locate Herbert Hein’s BuNo 1515 deeper inside Jaluit lagoon using clues gleaned from archival reports of Yorktown’s February 1942 raid. News that not one, but two, ultra-rare Douglas TBD-1 torpedo bombers survived in relatively accessible water depths sent shockwaves through the historic aviation community.

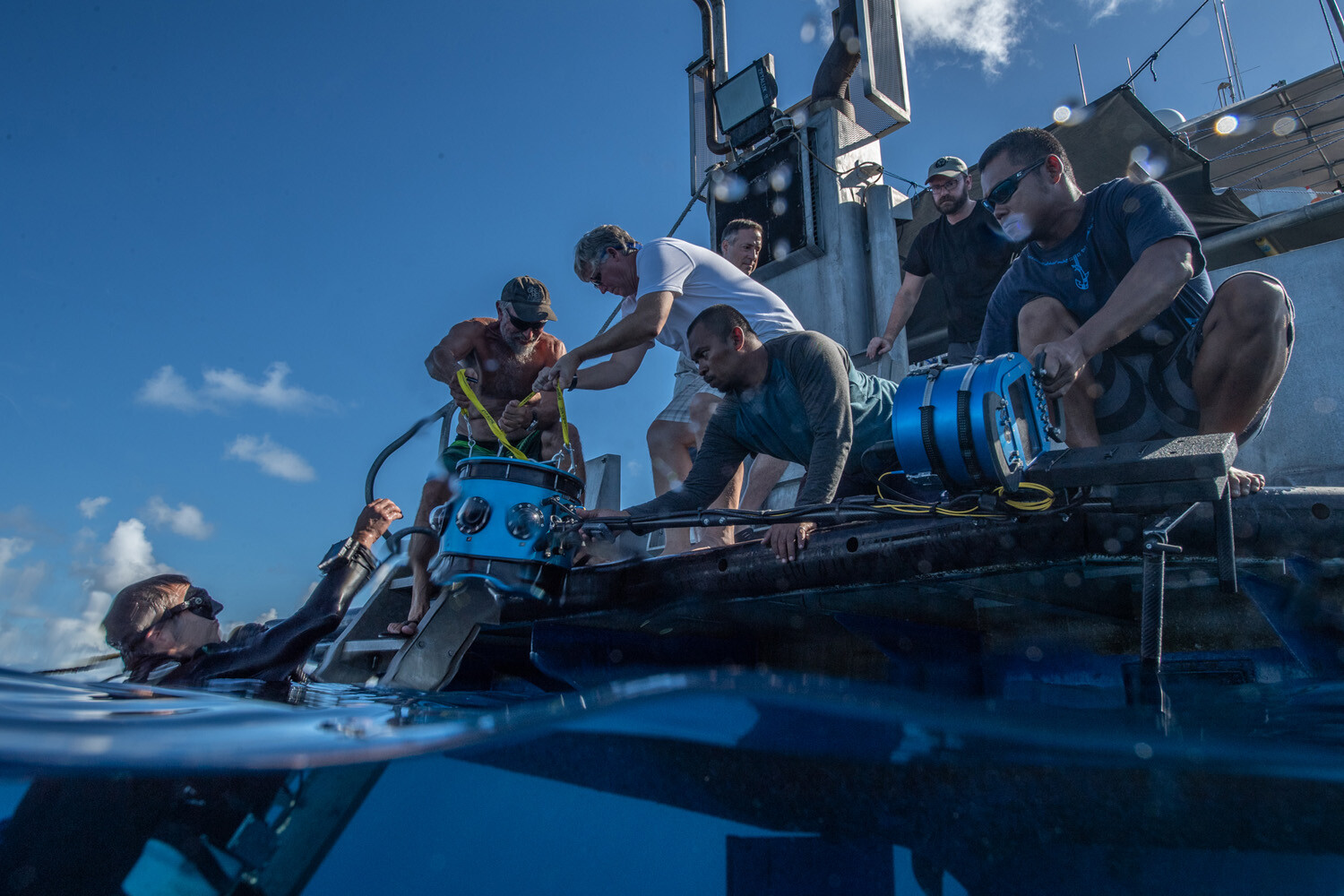

Seizing on this extraordinary chance to renew a lost legacy, The Devastator Project was inaugurated in late 2003, with the aim to fully document these special aircraft, regularly monitor their condition, and thoroughly evaluate the potential to recover and preserve at least one representative example of the type for future generations. Since that time, a growing team of highly dedicated and passionate archaeologists, historians, divers, engineers, conservators, and underwater imaging specialists has mounted no less than seven separate expeditions to the remote wreck sites, steadily coaxing the Jaluit TBD-1 wrecks to finally give up their secrets.

US Navy Douglas TBD-1 Devastator BuNo 1515

Often called “The Deep TBD,” in reference to its resting place roughly 120 feet beneath the surface Jaluit lagoon, the wreck lays level on a mostly sandy bottom with its starboard wing and a portion of the fuselage supported by some flat coral growth. Aside from the organic materials (such as fabric control surfaces and leather headrests) all of which were consumed by sea life and a few items missing since the initial ditching in WWII (like the tailwheel, flotation bag covers, bomb aimer’s door, Norden bombsight, and pilot’s map case) the airplane is almost entirely intact.

The upper engine mounts appear broken, probably from the aircraft hitting bottom in a nose-down attitude and resulting in the powerplant from the firewall forward tilting 9° downward and 20° to starboard. The outer 2.5 feet of one propeller blade is buried in the sand. No excavation has ever been attempted, but the exposed remainder and the entire length of the other blades show no indication of any damage

Fortunately, the aircraft exhibits no evidence of vandalism or pilferage since its arrival on the seabed more than eight decades ago. Both machine guns, the RDF loop antenna, cockpit controls/instruments, and all of the canopy elements are present and undamaged to the extent that can be determined without disturbing the site.

Its remarkable survival is likely attributable to a unique combination of factors; BuNo 1515’s position inside the lagoon and beyond the outer reef has sheltered it from storms and swells, while the greater depth means far less sunlight penetrates through the water column, in turn stunting the growth of corals and other marine organisms than can have an adverse effect on the manufactured structures. At the extreme edge of recreational diving, the deep site serves to limit the number of divers who can safely explore it. Devastator Project teams have rarely attempted such extensive work on the wreck without the reassurance of an onsite emergency decompression chamber.

That said, BuNo 1515 has not proved immune to the ravages of time and the inescapable degradation brought on by long immersion in seawater. The Devastator Project team has observed several areas of spreading corrosion taking hold along certain riveted seams, around the oil reservoir cap, and particularly in the aluminum outer skin covering the wing joints above the folding mechanism (likely the result of galvanic/differential metal reaction).

While this natural deterioration may be inevitable, the process has thankfully been slow, with very little change noted from one expedition to the next. The wreck has been repeatedly studied by experienced eyes and exhaustively documented with still images, 3D photogrammetry modeling, 4K video, virtual reality and subsea LiDAR scanning, which greatly assists in post-expedition comparisons and analysis.

All of the data collected by Devastator Project researchers has led to one inescapable conclusion; that BuNo 1515 represents the only Douglas TBD-1 known to exist that is both largely intact and reasonably accessible. It is, simply put, the world’s “last best hope” to preserve a genuine physical example of this iconic WWII aircraft for future generations.

US Navy Douglas TBD-1 Devastator BuNo 0298

As described in the previous section, TBD-1 BuNo 0298 was a squadron mate of BuNo 1515 on USS Yorktown and has likewise been the subject of extensive attention over the seven Devastator Rising expeditions. It is referred to most commonly by project team members as “The Shallow TBD,” again in reference to its position just 40 to 60 feet below Jaluit lagoon. In calm water, the sunken airplane can easily be viewed from the surface and is characterized most strikingly by its unusual attitude, hanging on the face of an inner reef at the far western edge of the atoll. It appears that, shortly after sinking, BuNo 0298 impacted the bottom and slid backwards down a steep underwater slope until its port wing jammed beneath an enormous coral outcropping with the starboard wing on a patch of barren sand, seemingly forever frozen in a perpetual 30° banking right climbing turn.

The brief, but violently dynamic contact with the seabed caused minor damage to the leading edge of the port wing as well as the port aileron which absorbed much of the force in arresting the wreck’s wild slide. More significantly, the engine ripped entirely away from its mounts and now sits forlornly 13.5 feet (as measured to the center of the propellor hub) from the accessories section in front of the stunted forward fuselage.

There is also the expected array of vanished organic material (leather and doped canvas) plus missing items likely lost in the initial ditching (flotation bag covers, tailwheel, etc) as seen on the Deep TBD. However, the first divers on site did note the conspicuous absence of the rear seat flexible mount Browning .30 caliber machine gun.

The missing gun was initially assumed to have been previously looted from the site, until summer 2004, when Devastator Project researchers found and interviewed James Dalzell, the WWII Navy veteran (sadly since deceased) assigned to that very position on the ill-fated final mission. Dalzell related that he removed the weapon himself before abandoning the sinking aircraft, thinking he and his crew might need it to defend themselves from the Japanese. He went on to say that when the fliers on 5-T-6 accidentally punctured their life raft, forcing all six men to rely on one rubber boat to survive, he threw the big gun overboard to make room for the others. He went on to speak movingly of the kind treatment received from the residents of Pingelap and stated that while resting in the shelter of a local house late that first night on the island he was overcome with a feeling of certainty (later proven 100% correct) that he and his comrades would be OK. The Devastator Project team was also fortunate to record the memories of the late Ambassador Carl Heine, who described the same remarkable events surrounding the Americans’ arrival, rescue, and peaceful surrender from his personal perspective as a small boy living on Pingelap in 1942.

James Dalzell and Ambassador Carl Heine shared their memories with Devastator Project researchers 62 years after the TBDs ditched at Jaluit.

Just as the residents of Jaluit once cared for the stranded US Navy fliers, so have their children and grandchildren helped to safeguard the now historic warplanes through local vigilance and the robust national antiquities protection measures enacted in the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). It turns out that by far the greatest impact on the submerged aircraft (and most especially BuNo 0298) through the intervening years has come not as the result of human interaction, but from the forces of Nature. While large swaths of the outer wing and fuselage skins on 5-T-7 remain cleanly pristine, other sections of the plane’s structure have been heavily colonized by stony (Pocillopora) corals. When the wreck was first characterized by National Park Service (NPS) divers in 1997, a couch-cushion sized coral growth was noted as having taken root, perched on the nose at the base of the radio antenna mast. Subsequent surveys by the Devastator Project team have tracked and documented its steadily accelerating expansion. As of the most recent dives (on 1 and 2 May 2023) the coral has grown exponentially, subsuming the radio mast as well as the pilot’s windscreen, completely covering the nose, nearly closing off access to the forward cockpit, and making significant inroads towards enveloping the auxiliary pilot/bombardier’s central crew position as well.

2003

2023

Side-by-side comparison of coral growth on BuNo 0298 shot twenty years apart (2003 photo courtesy John Hoover, 2023 photo by Brett Seymour

During the May 2023 assessment while making observations, taking still photographs and compiling material for a new 3D photogrammetry model, Air/Sea Heritage Foundation experts were dismayed to discover a major structural failure had occurred at the tail of BuNo 0298 since their previous visit to the site in 2018. The starboard horizontal stabilizer, formerly intact, was found to have separated cleanly from the fuselage at its attach points and hanging almost straight down to the bottom sand, connected to the airplane only by its internal control linkages. Again, this is not believed to be signs of willful vandalism, but rather the result of progressive corrosion in the bolts holding the stabilizer to the airframe which finally sheared under the pull of gravity and stresses imparted by the unusual angle of repose.

Conclusions

The latest developments with the Shallow TBD provide a stark preview of the fate in store for the Deep plane if no action is taken. And they are also the strongest conceivable argument for the notion that something must happen sooner rather than later, if a Douglas Devastator is ever going to be saved for the future. Fortunately, the unique circumstance of having two identical artifacts with nearly identical histories in such close proximity to each other means that it is actually conceivable to relocate one (BuNo 1515) for preservation and public exhibition, while retaining and managing the other (BuNo 0298) at Jaluit in situ and in context with its historical mission as a significant cultural heritage site and world class dive attraction.

It should be noted that all Devastator Project work at Jaluit Atoll has been conducted under permit and/or in partnership with the US Naval History & Heritage Command. The planes are considered American sovereign property in perpetuity and protected from unauthorized disturbance by the Sunken Military Craft Act. In addition, the wreck sites fall under the jurisdiction of the Republic of the Marshall Islands Ministry of Internal Affairs and permission for all archaeological activities was cleared and coordinated through the RMI Cultural & Historic Preservation Office (CHPO). Furthermore, every Devastator Project expedition has obtained the input and consent of Jaluit’s senators, mayor, and traditional island leaders, as well as dive permits issued by the Atoll local government. And finally, a rotating cadre of representatives from the CHPO and Jaluit Atoll Local Government (JALGovt) have been welcomed to observe any and all Devastator Project field operations to ensure full transparency.

Dive deeper – learn more about our mission by visiting one of the below topics.